What is Home Parenteral Nutrition (PN)?

Picture source: United for clinical nutrition

Home PN is the delivery of nutrient-enriched formula parenterally (other than via the mouth or gut) – commonly through a central venous access – on a long-term basis. Delivery can be rendered by patients themselves or their designated carer(s). The provision of parenteral nutrition, care and maintenance of the relevant elements associated this service are performed at home for the purpose of restoring and maintaining patients’ maximum level of comfort, function and health.

Prevalence of Home PN

Home PN programs started in specialised centres and rapidly developed into a growing experience with intestinal failures. In the early 1970s, Joyeaux and Solassol in France; Scribner in the United States; and Jeejeebhoy in Canada pioneered the use of intravenous feeding at home for the patient with gastrointestinal failure1-6. Since then, home PN has been used with increasing frequency in many large medical centres throughout the world.

Available data shows increasing confidence in home PN therapy and care. Certainly, when the landscape of long-term in-patient treatment is no longer cost-effective, home PN programs provide a new avenue for development of quality care without dependence on hospital-based support.

| Country | Population (m) | 2010 period prevalence (m) | 31st Dec 2010 point prevalence (m) | No HPN centres | Organized care | ||

| Referral pathways | Education programme | National guideline used | |||||

| Australia | 22.2 | 6.7 | 5.1 | 9 | No | Yes | AuSPEN |

| Belgium | 10.5 | 11 | 8(est) | 7 | No | No | ESPEN |

| Denmark | 5.3 | 66(est) | 47 | 3 | Yes | Yes | ESPEN |

| Rep of Ireland | 4.2 | 10.1 | 7.5 | 0 | No | No | ESPEN/NICE |

| England | 51.8 | 10 | 8.3(est) | 21 | No | Yes | ESPEN/NICE |

| France | 63.1 | 6 | Unknown | >14 | No | Emerging | ESPEN |

| Germany | 82 | Unknown | 49(est) | Few | No | No | ESPEN |

| Israel | 7.85 | 25.5 | – | 4 | No | Yes | ESPEN |

| Italy | 60 | 33.3(est) | Unknown | 90(est) | No | Yes | ESPEN |

| Netherlands | 17 | 14.7 | Unknown | 2 | Yes | Yes | ESPEN |

| N. Ireland | 1.7 | 18.8 | 14.1 | 1 | No | Yes | ESPEN |

| New Zealand | 4.2 | 7.2 | 5.3 | 1 | No | Yes | AuSPEN |

| Poland | 38.2 | 25 | 22.3 | 26 | Yes | Yes | None |

| Scotland | 5.3 | 23 | 17.5 | 11 | Yes | Yes | Standards |

| Spain | 46.2 | 3.25 | 2.7 | 7 | No | Yes | ESPEN |

| Wales | 3.0 | 18 | 21 | 2 | Yes | Yes | Standards |

Table 1. The populations, period and point prevalence data, the number of Home PN centres and whether referral pathways and organized care are in place

Who can benefit from Home PN?

The main indication for home PN is chronic intestinal failure. These patients cannot absorb the macronutrients (carbohydrates, fat and protein), micronutrients (vitamins and trace elements) and water needed to sustain life. Most cases of chronic intestinal failure result from massive small bowel resection due to trauma, thrombo-embolic events, inflammatory diseases and infectious diseases. There is also a large number of patient with abdominal cancer who have good progression-free survival, but the gut fails to function because of chronic obstruction or peritoneal disease.

| Definition

Intestinal failure is defined as the reduction of gut below the minimum necessary for the absorption of macronutrient and/or water and electrolytes such that intravenous supplementation is required to maintain health and/or growth. The reduction of gut absorptive function that does not require any intravenous supplementation to maintain health and/or growth, can be considered as “intestinal insufficiency” (or deficiency).

|

| Functional classification

On the basis of onset, metabolic and expected outcome criteria intestinal failures is classified as: Type I – Acute, short-term and often self-limiting condition; commonly after major surgery, among critically ill patients Type II – Prolonged acute condition often in metabolically unstable patients requiring complex multi-disciplinary care and intravenous supplementation over periods of weeks or months Type III – Chronic condition in metabolically stable patients requiring supplementation over months and years. It may be reversible or irreversible

|

| Pathophysiological classification

Intestinal failure can be classified into five major pathophysiological conditions which may originate from various gastrointestinal or systemic diseases – Short bowel: Generally defined as <150cm of residual small bowel – Intestinal fistula – Intestinal dysmotility – Mechanical obstruction – Extensive small bowel mucosal disease

|

Table 2. European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN) definition and classification of intestinal failure.

Intestinal failure in cancer

Cachexia (Picture source: Oncology Nurse Advisor)

A special mention is needed for intestinal failure in cancer. Palliative care in advanced abdominal cancer is mostly concentrated only on pain care while the nutritional status is left unaddressed. Unfortunately, many patients succumb to cancer cachexia rather than the disease itself.

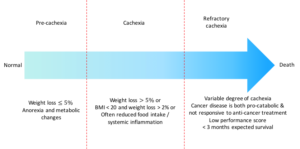

Fearon et al. defines cancer cachexia as a multifactorial syndrome characterised by an ongoing loss of skeletal muscle mass (with or without loss of fat mass) that cannot be fully reversed by conventional nutritional support and leads to progressive functional impairment7. The pathophysiology is characterized by a negative protein and energy balance driven by the combination of reduced food intake and abnormal metabolism.

Diagram 1. Types of cancer cachexia and its characteristics.

The cause of intestinal failure related to malignancy is most commonly bowel obstruction, followed by fistulation; short bowel resulting from surgery; infarction; or dysmotility. Bowel obstruction is estimated to occur in 10 – 28% of colorectal cancers and 5 – 50% of ovarian cancers8.

While most patients cannot be supported nutritionally, some are not in the refractory cachexia state and expected to survive more than 3 months. Also, the disease progression should have been rendered inactive from the palliative oncology therapy. These are patients who have good prognosis at maintaining quality of life. Therefore, nutritional support should be given continuously.

However, when Type III intestinal failure occurs in locally advanced abdominal cancers, the quality of life and life expectancy reduces dramatically. These patients usually succumb to severe dehydration if they are not treated early with parenteral nutrition. When hydration is well maintained, mortality is due to severe malnutrition before the progression to terminal disease.

One has to weigh the risks and benefits of parenteral nutrition support in this group of palliative cancer patients. As Fearon suggested in the model of cancer cachexia, optimal palliative care without commencement of PN would be the most appropriate intervention for recalcitrant cancer cachexia7. Commencement of risky, expensive and burdensome PN would be neither ethical nor acceptable to the patient. The challenge is, therefore, to optimally select patients according to the proposed characteristic of cancer cachexia and support only the ones whom the benefits outweigh the disadvantages of treatment.

Survival and Quality of Life with Home PN

Home PN is a “low volume/high cost” life preserving treatment for patients with intestinal failure. The high cost is expected; it is dependent on one’s healthcare system (partially funded or privatised), but also takes into account the ‘cost saving’ from allowing early discharge and all possible long-term in-patient complications. With better understanding of the bowel physiology and its adaptation phase, more patients are being treated with home PN with good quality of life and longer life expectancy. Intestinal transplantation is currently reserved primarily for those with home PN-associated complications.

| Treatment modality | Description

(Period of review) |

Authors | 1

year |

3 years | 5 years | 10 years |

| Home PN | Series of 40 patients excluding malignancy

(1986 – 2001) |

Pironi L et al. Dig Liver Dis 2003; 35 | 97% | 82% | 67% | |

| Series of 268 patients with SBS and excluding malignancy

(1990 – 2006) |

Amiot A et al Clin Nutr 2013; 32: 368-374 | 94% | 70% | 52% | ||

| Patients of Crohn’s disease extracted from multiple series

(NA) |

Pironi L et al. Clin Nutr 2012; 31: 831-845 | 88% | ||||

| Series of 60 patients with Crohn’s disease

(1979 – 2003) |

Lloyd DA et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2006; 24: 1231-1240 | 87% | ||||

| Intestinal tx | Series of 453 patients

(1990 – 2008) |

Abu-Elmagd KM et al. Ann Surg 2009; 250: 567-581 | 85% | 61% | 42% | |

| Series of 687 patients

(1987 – 2009) |

Desai CS et al. Trans- plantation 2012; 93: 120-125 | 77% | 61% | 51% | ||

| Series of 86 patients with Crohn’s disease

(1987 – 2009) |

Desai CS et al. Transplant Proc 2013; 45: 3356-3360 | 79% | 53% | 43% |

Table 3. Survival comparison between Home PN and Intestinal Tx (intestinal transplantation) in intestinal failures.

Picture source: findingmymiracle.com

Either curative or palliative treatment cancer patients’ nutritional status should be intervened with patient-tailored nutritional care plan. Nutritional intervention during the curative oncology therapy increases the tolerance and response to the oncology treatment, decreases the rate of complications and possibly reduces morbidity by optimising the balance between energy expenditure through stress from the therapy and a nutrition support9.

On the other hand in palliative oncology therapy, nutritional support aims to improve patients’ quality of life by controlling symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, pain or uneasiness related to food intake. Therefore with undeterred nutrition support, especially with parenteral nutrition, the palliative oncology therapy can continue without interruption. At the same time, it can minimise the overall catabolic impact of cancer cachexia9.

What About Infections?

The pretext of ‘risk of sepsis’ when the patient is infused with chemotherapy and parenteral nutrition concurrently is totally unfounded. The poor practice of strict catheter care bundle and handling of parenteral nutrition formula bags (from the pharmacy to the bed) are the 2 leading factors to sepsis among these patients. Selection of robust central venous catheter too will ensure long-term durability of these venous access and its related care. Sadly the knowledge and practice on these pertinent issues are still poor among our clinicians and nurses.

Health Economics and the Home PN program

Although clearly an expensive therapy, the cost of parenteral nutrition is offset by its life-sustaining nature, out-of-hospital care and all the possible cost related to care and complications in the hospital.

Two major studies looking at the cost utility or assessing efficiency of treatment and monetary values based on quality-adjusted life year (QALY) gained have shown that home PN is much cheaper economically by £69,000 and $14,600 in the UK and Canada respectively, compared to long term hospitalized parenteral nutrition (table 4)10.

| Study | Country (year) | Methodology | Findings |

| Richards, 1996 | UK (1995) | Cost-utility analysis | First year cost of Home PN is £44,288. The marginal cost per QALY was £69,000. One year of hospital TPN cost £93,000 |

| Detsky, 1986 | Canada (1970 – 82) | Cost-utility analysis | Marginal cost per QALY was $14,600. Increase of 3.3 years of quality-adjusted survival compared with hospital nutrition support. |

Table 4. Cost utility analysis of marginal quality-adjusted life years (QALY) between home PN and in-patient parenteral nutrition.

In North America, home PN is estimated to cost USD64000/year11. In the United Kingdom, it costs £30-40000/year, for 5 days/week therapy if self-caring if opted, or £55-65000/year if requiring nursing support12. That would translate to anything between RM220,000 to RM250,000 in Malaysia. Comparatively intestinal transplantation in the United Kingdom is estimated to cost £80000 in the first year (about RM 440,000), followed by £5000 annually. Thus, assuming no complications arise from this surgery and its long-term care, intestinal transplantation should only be cost-effective after 2 years13.

Home PN in Malaysia

Pertinent to any nutrition care plan is not only the formula calculation but safety of its delivery. Nutrition Therapy Teams (NTT) are trained to look after the care process to ensure there are no related complications during the delivery of the nutrition care plan and, more importantly, the expected clinical outcome is achieved.

Planning for home PN requires an extensive evaluation by the NTT. It involves not just the clinical aspects but also environment, logistic and training issues. NTT is the best platform where multi-professional experts in their fields manage the patient with a team-based approach, backed by the latest and evidence-based benchmarks in a dedicated one-stop centre.

The NTT in Hospital Sungai Buloh has been supporting the training of almost all NTTs in Malaysia since 2009. We embarked on the home PN program in 2015 as an effort to reduce the bed constraints and provide the opportunity for patients to recuperate in their home, surrounded by their loved ones.

We have managed 16 cases of home PN and potential home PN since we started. The first few cases deceased after less than 20 days at home. However this was largely contributed by the fact that preparation of home PN took longer than expected as we were inexperienced then. Those patients were treated with PN as in-patients for more than 3 months before they were discharged.

As we progressed, we faced challenges to execution such as no potential responsible care taker or the home environment was not conducive for home PN. Majority of patients with short bowel syndrome reverted with good bowel adaptation hence they managed to be independent from PN. Most of the cancer cases managed to complete their adjuvant oncology therapy

We strongly encourage a basic training program – based on PENSMA (Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition Society of Malaysia) and ESPEN (European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism) modules – as well as an attachment in our unit, for any team embarking on a home PN program.

Conclusion

Poor grasp in the basic knowledge of intestinal failure/short bowel syndrome has led to high morbidity and mortality when they should be salvageable cases with potential for independence from artificial nutrition. Providing palliative or curative adjuvant oncology therapy without nutrition support will aggravate cancer and catabolic weight loss from non-effective anti-cancer therapy while increasing the susceptibility towards high anti-cancer toxicity, non-compliance, non-respondent and non-completion.

Home PN offers continuous nutrition support hence preventing protein-energy malnutrition with acceptable vital organ functions to recuperate from intestinal failure as well as endure the toxicity of anti-cancer therapy. The health economics is very favourable and there is improved quality of life, not experienced with conventional therapy.

We need more Nutrition Therapy Teams in Malaysia. Having them on board will certainly help to facilitate home PN programs. With only one centre providing home PN (for adult patients), it will be difficult to manage the influx of referrals. There is a long way to go, but we are definitely on the right track.

Dr Shukri Jahit

Consultant Upper GI Surgery & Nutrition Therapy Team

Department of Surgery, Hospital Sungai Buloh

[This article belongs to The Malaysian Medical Gazette. Any republication (online or offline) without written permission from The Malaysian Medical Gazette is prohibited.]

References:

- KN Jeejeebhoy, B Langer, G Tsallas et al. Total parenteral nutrition at home: studies in patients surviving 4 months to 5 years.Gastroenterology 1976; 71(6):943–953

- C Solassol, H Joyeux. A compact portable prosthesis for total parenteral nutrition (T.P.N.): ambulatory parenteral feeding in the hospital and home.Acta Chir Scand Suppl 1976; 466:78–84

- K Ladefoged, S Jarnum. Long-term parenteral nutrition.Br Med J 1978 Jul 22; 2(6132):262–266

- PJ Milewski, E Gross, I Holbrook et al. Parenteral nutrition at home in management of intestinal failure.Br Med J 1980 Jun 7; 280(6228):1356–1357

- WJ Byrne, ME Ament, M Burke, E Fonkalsrud. Home parenteral nutrition.Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1979 Oct;149(4):593–599

- M The advent of home parenteral nutrition support. Ann Rev Nutr 2010; 30:1-12

- K Fearon, F Strasser, SD Anker et al. Definition and classification of cancer cachexia: an international consensus. The Lancet 2011; vol 12 (5):489-495

- Ripamonti C, De Conno F, Ventafridda V, Rossi B, Baines MJ. Management of bowel obstruction in advanced and terminal cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 1993;4(1):15-21.

- MM Caro, A Laviano, C Pichard. Nutritional intervention and quality of life in adult oncology patients. Clinical Nutrition 2007; 26, 289–301

- DM Richards, JJ Deeks, TA Sheldon, JL Shaffer. Home parenteral nutrition: a systemic review. Health Technol Assess. 1997;1(1):i-iii, 1-59.

- U Piamjariyakul, VM Ross, DM Yadrich, AR Williams, L Howard, CE Smith. Complex home care: Part I – Utilization and costs to families for health care services each year. Nurs Econ 2010; 28: 255-263

- http://www.specialisedservices.nhs.uk/library/26/Specialised_Intestinal_Failure_and_Home_Parenteral_Nutrition_Services_adult

- http://www.organdonation.nhs. uk/newsroom/bulletin/pdf/bulletin_2008_spring.pdf.