Source: blog.treatmentassistance.in

- Thalassemia is in fact a Greek word. The word “Thalassa” means sea and “Emia” means blood.

- It is a genetic disorder inherited from either or both of your parents.

- It is the commonest single gene disorder in the global population .

- In Malaysia, it is estimated that 1 in 20 people is a thalassemia carrier.

- The disorder primarily affects your red blood cells (RBC) resulting in reduced or absent production of haemoglobin –the oxygen carrying vehicle in your body resulting in a medical condition known as anaemia.

- Simple concepts about heredity that you need to know.

- In every generation, genes are shuffled and re-shuffled. Half of your genetic make up comes from your father and the remaining half comes from your mother.

- Eye color is an example of inherited characteristic, i.e. assuming that the roots of your family trees are “purely”Asian, that explained why you have “brown eyes” instead of blue eyes.

- Similarly, this concept is applicable in thalassemia gene inheritance.

- There is one important term that you need to be clear of to understand how thalassemia is inherited , i.e. ‘thalassemia carrier’.

- A thalassemia carrier is a person who has a copy of the thalassemia gene.If you are a carrier, most of the time you will appear healthy and do not manifest the symptoms of thalassemia. However, a carrier can pass the abnormal gene to the future child (remember it was mentioned earlier, every individual carries one copy of gene from the mother and one from the father).

- So now, find out what are the chances of your offspring inheriting the thalassemia gene by continue reading this article.

- “I am perfectly healthy and so was my family member…it seems to me ignorance is bliss”

- Have you gone for thalassemia screening? If your answer is NO, perhaps you should visit the nearest clinic soon because your present decision might have a great impact on your future generation.

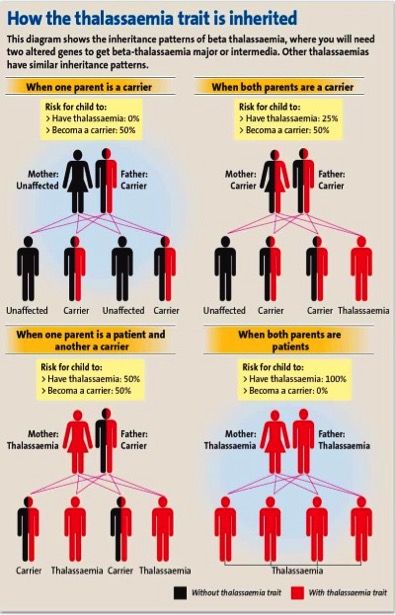

- In a situation where there is one parent carrier ( assuming you are a carrier and your partner is a normal individual), the chances of having a normal child or a thalassemia carrier child is 50% respectively (Refer to Diagram).

- The situation has become very much different if the couples are both carriers. There are 3 possibilities of your child’s genetic inheritance outcome; normal individual (25%), carrier (50%) or affected individual (25%) – also known as thalassemia major that will be blood transfusion dependent (Refer to Diagram).

- When one parent is an affected individual (thalassemia major patient) and the partner is a carrier, all your offspring will carry a thalassemia gene. Thus, you will not have a normal invidual. Your child will either be a carrier (50%) or affected individual (50% – thalassemia major).

- If both couples are thalassemia major individual, all of your offspring will be affected individual (100%)

HOW THALASSEMIA GENE IS INHERITED

The following diagram shows the inheritace patterns of all types of thalassemia i.e alpha(α) or beta(β) globin chain gene defect

- What can you do to determine if you are a thalassemia carrier?

- Thalassemia carrier is usually a healthy individual.He/she does not manifest sign and symptoms of thalassemia and therefore undetected most of the time.

- Thalassemia CAN ONLY be detected and confirm by blood test.

- For the initial screening, widely available in private and government clinics, a full blood count will be suffixed to rule out the risk of thalassemia carrier.However, haemoglobin analysis or DNA analysis will give you a confirmatory diagnosis of your thalassemia status.

- One will only need to undergo thalassemia screening once in your lifetime as your status will not change overtime.

- As discussed earlier, thalassemia is a genetic disorder (your child has a chance of inheriting thalassemia gene) and if you are a healthy carrier it might go undetected giving you a false sense of assurance of your status.

- Thalassemia patient- What they go through for the rest of their lives?

- Thalassemia patient, most of the time, shows the disease manifestation few months after birth. The child is typically pale (anaemic) and have failure to thrive.

- They are blood transfusion dependent for survival-MONTHLY basis and at times it maybe on weekly basis, depending on the individual.

- Due to the frequent blood transfusions, they are at risk of iron overload that leads to vital organs damage such heart and liver failure.

- Bone marrow transplantation is the only cure, but finding a suitable donor is challenging and very much depending on the medical expertise available.

- Success story from Iran Thalassemia Pre-marital Screening Program

- The number of carriers detected has increased from 0 in 1000 to 4.1 in 1000 population2.

- After 20 years of the compulsory premarital screening program, study found that the birth prevalence of beta thalassemia child reduced 30 % in Iran1.

- The most important benefit of premarital screening is that it gives thalassemia carriers and carrier couples the possible range of informed choice and decide on their current or future pregnancy.

- In our country, thalassemia screening program is not compulsory but you are encourage to go for screening.

- To summarise what you need to know about thalassemia

- Thalassemia is preventable.

- Screening is easily and widely available .

- Thalassemia carriers are most of the time perfectly healthy individuals, BUT are capable of transferring the genes to their offspring.

- Regular blood transfusions with other treatment (iron-chelation) ensure the survival of thalassemia patient.The only cure for thalassemia patient is bone marrow transplant.

- Eventhought treatment is available, we believe that “Prevention Is Always Better Than Cure” and thalassemia is definitely a highly preventable condition.

Dr. Sharon is currently a health administrator in Sabah who greatly believes in empowering the public with health awareness.

[This article belongs to The Malaysian Medical Gazette. Any republication (online or offline) without written permission from The Malaysian Medical Gazette is prohibited.]

References:

- Zeinalian et.al (2013) Two decades of pre-marital screening for beta-thalassemia in central Iran. Journal of Community Genetics Volume 4 (4) , pp 517-522

- Samavat and Modell (2004) Iranian thalassemia screening programme. BMJ 329;1134-113