Picture: www.webmd.com

Relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD) test is a common screening tool used by medical personnel in the ophthalmology clinic when seeing newly referred cases. It is done routinely prior to consultation with a medical officer. Even medical students are reminded to perform the RAPD test as part of a complete cranial nerve examination. Despite its wide application, many still do not understand the real function of the RAPD test and wrongly interpret its results.

Is it possible to identify the normal or abnormal eye based on the result of the RAPD test? To correctly answer this question, we need to have a closer look at how our eyes work.

The pupils constrict in response to light and dilate in absence of light, a phenomenon known as the pupillary light reflex. The beauty of this is that both pupils will constrict even if only one eye is stimulated by a light source. This is called the consensual light reflex. It requires an intricate coordination between various components of the visual pathway; the optic nerve transmits impulses from retinal photoreceptors to the midbrain, impulses that then travel to the ciliary ganglia via the oculomotor nerve and cause equal constriction of both pupils.

It is important to note that perception to light depends not only on healthy optic nerves but also functioning photoreceptors of the retina. A damaged retina will only have partial or no perception to light, which will affect the quality of pupillary constriction of both eyes due to the consensual light reflex. This is regardless of the intensity of light used.

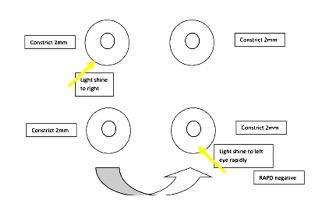

As its name suggests, the RAPD test compares the size of each eye’s pupil relative to one another. It is performed by shining a light source into each eye rapidly (“swinging light test”) and determining the equality in pupillary constriction. In essence, the RAPD test measures the perception of light in the examined eye.

Here are two scenarios to demonstrate the application of the RAPD test. To understand them better, it is necessary to take note of the following: good perception to light leads to pupil constriction to 2mm; partial perception 4mm; and no perception results in pupil dilatation to 6mm or more.

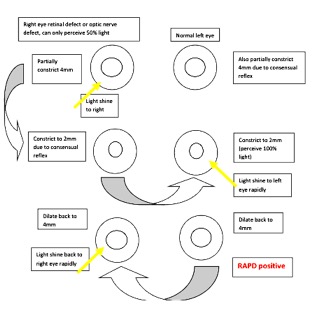

Scenario 1

The right eye has a retinal defect and can only detect 50% of light while the left eye is normal. Despite an adequate light source, the right pupil only constricts to 4mm. The left pupil also constricts to 4mm due to the consensual light reflex. However when the light source moves to the left eye, it constricts fully to 2mm and the right pupil further constricts to 2mm as well. Upon swinging the light source back to the right eye, the right pupil can be observed to dilate from 2mm to 4mm as it only has partial perception to light. This is called RAPD positive.

The conclusion then is that the right eye is abnormal. Although it is the correct diagnosis in this case, can the same be said every time?

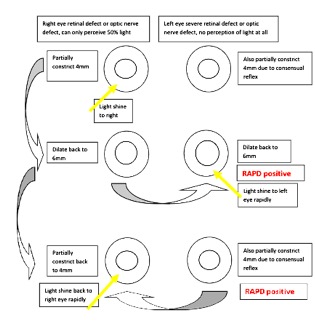

Scenario 2

Consider a situation where both eyes have abnormal perception to light. The right eye can perceive 50% of light while the left eye has no perception to light at all. If light is shone through the right eye, both pupils partially constrict to 4mm. Once the light is shifted to the left eye, both pupils dilate to 6mm.

In this case it is also RAPD positive, but is it possible to identify which eye is normal and which isn’t? The answer is no, because the truth is that both eyes are abnormal. However, can we infer which eye is better? Yes, we can come to the conclusion that the right eye function is relatively better than the left.

From these two scenarios, it is clear that the RAPD test only identifies the relative equality of pupillary constriction in response to light. When RAPD is positive, it is possible to conclude that one eye is relatively better compared to the other, but we are unable to rule out whether pathology is present in only one eye or if both have defects.

It would therefore be more accurate to change the title of this article to “RAPD Positive: Which eye is relatively better?”!

This article was written by Dr Mohd Shaiful Ehsan.

Dr. Mohd Shaiful Ehsan is a family medicine master trainee in the International Islamic University Malaysia.

[This article belongs to The Malaysian Medical Gazette. Any republication (online or offline) without written permission from The Malaysian Medical Gazette is prohibited.]